|

We can characterize US consumer culture by apparent and indulgent personal freedoms, but this freedom is manipulated by an ever-present media that influences actions far more effectively than traditional authoritarian structures ever could. What’s more, this total control is in accordance with the needs of industrialization and the corporation and is often directly opposed to the needs of society and the environment.

The state no longer uses propaganda exclusively to brainwash the public into its nationalist framework. Propaganda is now decentralized, pushing people in many different directions at once, encouraging an increasingly fragmented culture, but with a surprisingly consistent directive. Propaganda exploits the limit to our understanding, our inability to grasp all of the knowledge in the world at the same time, our resort to heuristic determinations based on believing who we trust, and even worse, copying what others around us do, say, and believe. If you were to ask people if they are influenced by the torrential amount of propaganda they are subjected to from the media and advertisements, most would deny that there is any influence whatsoever. Because propaganda is ubiquitous in our culture it has become invisible, like the air that we breathe. Since the effect on all of us is uniform and we have no way to compare with people within our culture who are unaffected, it is difficult to measure. Advertising explicitly promotes the product. Secondly, it implicitly promotes a type of product: cigarette advertising makes smoking look cool. Thirdly, advertising promotes a set of values, including instant gratification and that doing what makes you happy is the best option. These values are often not the same as the values of society. For the media, delayed gratification is counter-productive. Considering the consequences of present actions is similarly irrelevant. Advertising presents leisure as better than work and the democratically elected government, rather than the undemocratic corporation as the source of oppression. Capitalism, unlimited production, and unrestrained economic freedom in the market place have led to a distortion of traditional values. Much of what constituted good character in ages past — such as persistence, hard work, and the value of delayed gratification — the ever-present media has subverted. Laziness is now a virtue and immediate gratification is just good mental health. Individual freedom of the greediest and most powerful now supersedes the freedom that all people used to have. Nowhere is this manipulation of behaviour more apparent than in marketing to children. For kids, marketers convey the view that wealth and aspiration to wealth are cool. Material excess, having lots of money, career achievement, and a lifestyle to go with it are all highly valued in the marketing world’s definition of what’s hot and what’s not. Juliet Schor in Born to Buy concludes, “Children have become conduits from the consumer marketplace into the household, the link between advertisers and the family purse…. Living modestly means living like a loser.” Marketers have also created a sophisticated and powerful “’antiadultism’ within the commercial world.”[1] Nickelodeon, for example, promotes “… an antiauthoritarian us-versus-them sensibility that pervades the brand.… In the kid-centric hip world, adults are the bothersome, the nerdy, the embarrassing, and the repressive.” Behaviour is promoted that is “annoying, antisocial, or mischievous.”[2] As children grow and mature, they have a natural tendency to separate from their parents, to be contrary and oppositional for a while, ultimately finding their own character. Advertisers have exploited and capitalized on this tendency and exaggerated it to great detriment to our society. Whereas our parents wanted to save and not waste, we have learned to consume more and not waste the opportunities presented in the media for greater happiness. Our children, with the media’s ever-present encouragement, have turned consumption into a form of cultural expression. The media perverts even the urge to be ecologically friendly, taking a moral imperative to consume less and diverting it into a guilt-free mandate to consume more “green” products in even more elaborate, but “greener” packaging. While you can find people in the United States who have rejected this work-and-spend lifestyle, few of these “downshifters” have children. The modern media as the instrument of the modern corporation, isolated from democratic influences, has hijacked our culture, stolen the hearts of our youth, and now threatens our future. Fascism is associated with far-right politics, but in reality, it is a populist union of various right and left ideals. In contrast with other totalitarian governments, fascism is born from a movement within an otherwise democratic society. It depends on popular support and ongoing recruitment for its power. Policies are crafted, not out of a consistent ideology, as in communism, but of a mixture of traditions and prejudices of the populace. It includes the corporations that have grown larger, more powerful, and more independent of the democratic influence of government but able to influence huge sections of the populace with powerful propaganda now called marketing. Corporations also grow in size and naturally resist the democratic control of governments. There is now more danger of surveillance, control, and oppression from the likes of Apple, Microsoft, Google, or Facebook than from any democratically elected government. Governments may be imperfectly controlled by representative democracy, but corporations are hardly controlled at all. Fascism is primarily a philosophy of exclusion, responding to natural tribal propensities to join groups and to exclude those that refuse to join or are different. As such, it can become fiercely nationalistic or racist. Policies can range from the extreme left to the extreme right. Born out of democratic conditions, it may ultimately condemn representative democracy as lacking in decisiveness and requiring too much compromise. What is ultimately asked for and willingly given by those who join fascist movements is unquestioning acceptance to evolving ideals and charismatic authority. There is much in current popular culture and especially the child-centred, brand-motivated culture of creating the idea of cool, which suggests a fascist sensibility in the works. Neil Postman suggested in 1985 that media such as television (or now the internet) is ideology because it imposes “a way of life, a set of relations among people and ideas, about which there has been no consensus, no discussion and no opposition.”[3] Such technology has succeeded far more effectively than Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf did in creating a new culture that excludes traditional values. “Huxley grasped, as Orwell did not, that it is not necessary to conceal anything from a public insensible to contradiction and narcoticized by technological diversions.”[4] The welfare state, in contrast, represents a philosophy of inclusion, accepting all races, all religions, and even all points of view as valid. It is internationalist rather than nationalist and seeks a global solution to problems such as poverty, global warming, and pollution. It is a democratic union of the right and the left — a series of compromises that allow socialist and statist institutions to coexist with free markets and competitive corporations. The ideals of the left and the right sit in an uneasy compromise, shifting one way and then the other according to the practical needs of the economy. It is the official, accepted form of government for most of the developed world, but it rests on a sea of conflicting and contrary popular sentiments, and entrenched political views that seek to dismantle what has been built over the past century. There is no reason for all industries to be privatized. Nationalized education, transportation, healthcare, postal service, and police protection are sustainable and in many ways create conditions more beneficial for society. Private healthcare in the United States is a disaster. Transportation networks devoted to the automobile have resulted in hopelessly clogged streets and ruined cities. Limited public radio and television has resulted in a consumer culture nearly devoid of social or environmental responsibility and devoted almost exclusively to diversion and play. The proposal here presented is that we maintain and extend the institutions of the welfare state, including universal distribution of essential goods and services. To control markets effectively and to solve the many and complex problems that emerge, governments will likely have to be larger, not smaller. The only alternatives of smaller governments and more power to individuals will increase the power of corporations and special interest groups, and make a return to fascism that much more likely. The welfare state is not a brief experiment that failed, but the extension of the city-state that is the very basis of civilization. Rather, the neoliberal experiment of completely free markets was brief, and failed miserably. In reality, the welfare state, including the enlargement of government and institutions such as universal pensions, employment insurance, and welfare programs offering a safety net for the growing threat of job loss and unemployment, is what was responsible for the growing prosperity from 1950 to about 1973. The recent restrictions on the growth of the welfare state have limited prosperity to a few and threaten to dismantle the whole edifice. There is great suspicion and prejudice of big government, but a large welfare state is not just a necessary evil, it is more efficient for the operation of a large part of the economy that involves the universal distribution of essential goods and services. In the last century, industrialization, automation, and outsourcing drove down wages and increased unemployment. Economic growth and the growth of the service industries have replaced some of this job loss, but not all. Unemployment has grown, and wages for 80 percent of the population have not kept pace with what one would expect from the economic growth that has occurred. The welfare state has grown in reaction to these trends. First, the growth of government provides more jobs, replacing many lost in manufacturing. Secondly, government programs provide funding for research projects and universities, which have been responsible for the spontaneous development of new industries including computers, the internet, biotechnology, and many more that will come on line in the next century. Government subsidization has also made it possible for immature industries to develop, and for individuals to take more risks in the search for a career and additional education. [1] Juliet B. Schor, Born to Buy, (New York, London, Toronto, Sydney: Scribner, 2004), 11, 48, 51. [2] Ibid 52–54. [3] Neil Postman, Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business, (New York, London: The Penguin Group, 1985), 157. [4] Ibid, 111.

1 Comment

Introduction

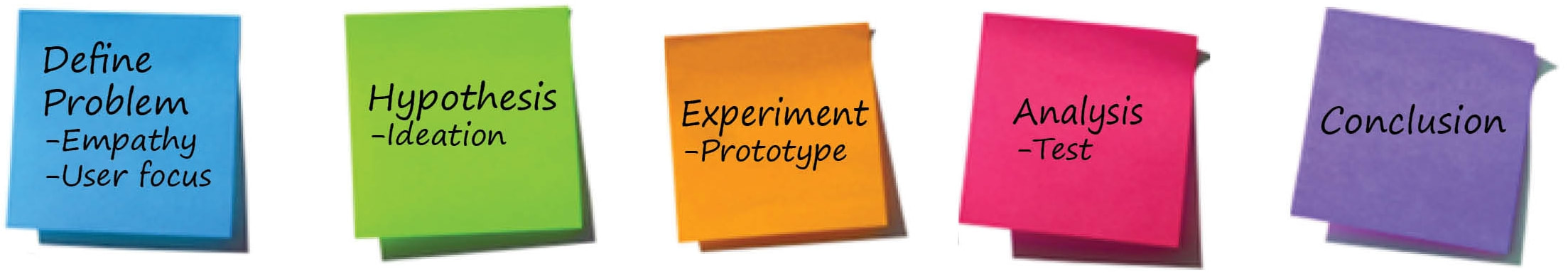

If there are wicked problems, there must also be good problems and also, perhaps, bad problems – those not quite so wicked. If there is such a thing as design thinking, there must also be other types of thinking. Is there a form of thinking that is used by designers that is different from other forms of thinking? Is it possible to design without thinking? The phrase design thinking originally referred to how designers think, a way of thinking about complex (wicked) problems – problems that are poorly defined and intertwined with solutions, a definition suggested by Horst Rittel, a mathematician, design theorist, and university professor at the Ulm School of Design in Germany in the 1960s (Rittel, 1973) and later elaborated by Richard Buchanan (1992). Such thinking is routinely used by expert designers, artists, and craftsman. However, in recent years, the phrase has been hijacked by the likes of IDEO and Stanford University’s design school (called d.school), to refer to a simple design process that can be easily taught to novices in a couple of days. Blogger Lee Vinsel compares the corporate spread of design thinking to the spread of an infectious disease, and suggests that design thinking as it is now taught in schools is “not about innovation in any meaningful sense; it is about commercialization – a package sold by consultants and universities.” (Vinsel, 2017). Natasha Jen, a partner at the design firm Pentagram, in her talk “Design Thinking is Bullshit,” complains that design thinking has become a meaningless buzzword and facetiously suggests that the complex process of design has been reduced to a single tool, the 3M Post-It note. She notes what is often missing is critical thought (Jen, 2017).

Jon Kolko, more sympathetically, describes the current practice of design thinking as a “human-centred approach to innovation that draws from the designer’s toolkit to integrate the needs of people, the possibilities of technology, and the requirements for business success.” Empathy, the participation of users, and experimentation with low resolution prototypes are important aspects of design thinking. Unfortunately, he laments, there are now two paths of design that are diverging: practicing designers practicing design by making things and other people practicing design thinking. He stresses that making has a formal depth, and form has ties to aesthetics, history, meaning, and people. Design has become a cultural phenomenon, a lens for human experience, a means to humanize technology, while design thinking, as currently practiced, is designing without the rich skills of designers. Design thinking programs are characterized by 2-hour subject interviews, chaotic working sessions, a relentless pursuit of newness, a lack of craft skills, and positive thinking at the expense of critical thinking. In his paper “The Divisiveness of Design Thinking,” Kolko provides a decent summary of the various criticisms of design thinking: it oversimplifies a complex process; it trivializes the craft of making things; it reduces complex and meaningful connections of people to a simple attitude called empathy; and has become a tool of consultancies and universities to sell more work. In spite of this, Kolko thinks that the current popularization of design thinking has helped designers. He writes that “designers have recognized impact and it’s not about styling. It’s strategic.” He claims we can get more meaningful work by stomaching the superficiality of design thinking and riding its wave of popularity.

I am not so sure. The way design thinking is commonly presented is intellectually confusing on three levels. Firstly, it borrows heavily from the Scientific Method and would be more appropriately labelled “a” design method. Insisting on empathy as a step and the participation of users suggest that it is more specifically a human centred design method.

Second, the method promises innovation as a result, with ideation – a non-critical generation of as many ideas as possible – as a central feature. This suggests that design thinking, as the phrase is used, is a technique, not unlike brainstorming. Third, design thinking, since it leads to a result at the end of a process, is indistinguishable from a design process. If the idea is to compress the design cycle, then a term like “sprint” as suggested by Jake Knapp as a five day process “to solve big problems and test new ideas” (Knapp 2016) would seem more appropriate.

Design thinking has been branded as a technique for generating ideas, not unlike brainstorming as a method for solving a design problem in a human-centred way, and as a tightly controlled collaborative design session more like a charrette. This suggests an idea that promises far more than it delivers, yet fails to define its true essence. The current commercialization of design thinking makes design in a formal sense less relevant and more commodified in the long run. Although frequently added to education curriculums, the watered down technique falls short of goals of early design theorists such as Bruce Archer, that design should stand equal to the humanities and the sciences (Archer, 1965).

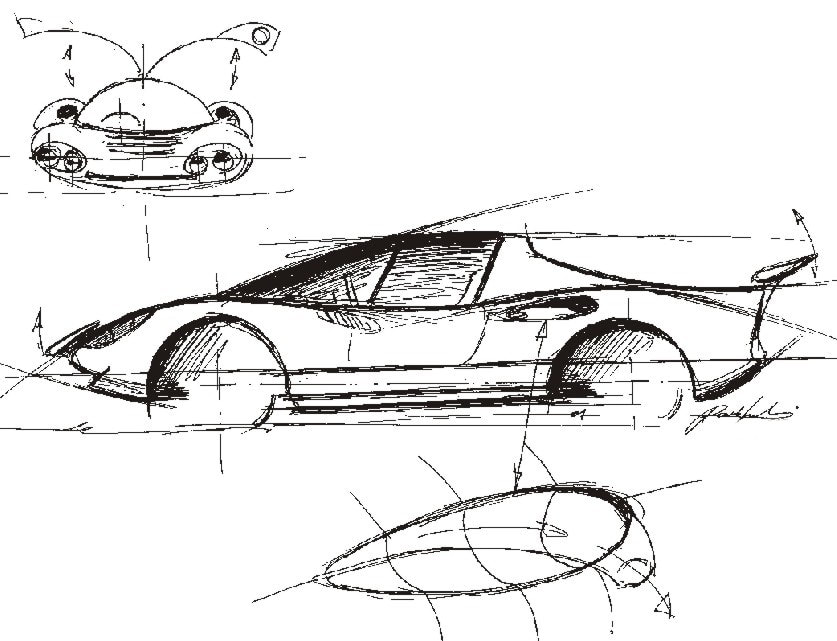

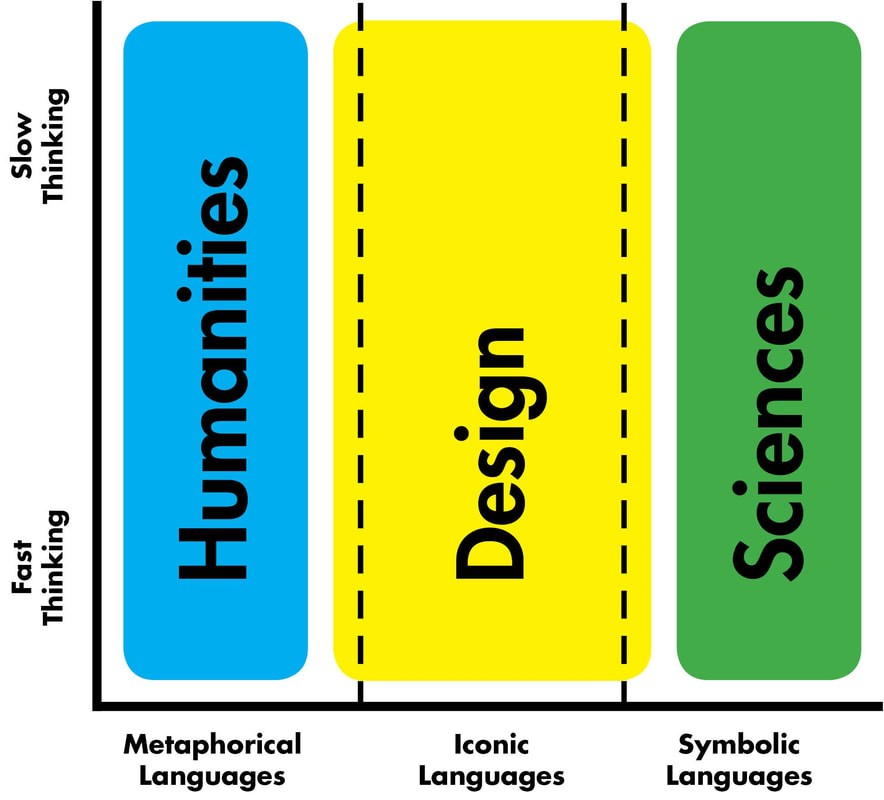

The original purpose of the term design thinking was to understand and define the process of design in a theoretical sense, not as a separate activity that is almost the same as design but different. The use of the term now suggests that it is design-like thinking applied to problems not normally thought of as design problems. This is problematic in that it implies that other design problems do not require design thinking. The process of design thinking as presented by d.school is a caricature of a formal design process – it exaggerates empathy and user participation, while compressing idea generation and experimentation. Instead of being the way expert designers think, design thinking has become the way novice designers or non-designers design. The way design thinking is currently used is quite different from the way early theorists used the term. In his 1973 paper “Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning”, Horst Rittel described the nature of wicked problems but never used the term “design thinking.” Bruce Archer is credited with the first use of the term “design thinking,” but the actual quote “Ways have to be found to incorporate knowledge of ergonomics, cybernetics, marketing, and management science into design thinking” suggests the thinking related to design rather than design thinking as an activity distinct from design (Archer 1965). Bryan Lawson discussed solution-focused problem solving approaches of designers in his book How Designers Think (Lawson 1980). In Design Thinking: Understanding How Designers Think and Work, Nigel Cross uses the term “design” and “design thinking” interchangeably suggesting that design thinking is how expert designers thought about a design problem and that this is integral to the design process. (Cross 2011). Richard Buchanan writes in the introduction to his well-known article "Wicked Problems in Design Thinking," “Despite efforts to discover the foundations of design thinking in the fine arts, the natural sciences, or most recently, the social sciences, design eludes reduction and remains a surprisingly flexible activity.” Here, the use of the phrase design thinking simply refers to thinking about design rather than as a separate type of activity. The phrase design thinking is used extensively in the article, sometimes to indicate how designers think while they are designing, and at other times to refer to the thinking about design issues or the profession of design. Buchanan describes four areas of design to show how design extensively affects contemporary life: design of visual communication; design of material objects; design of activities and organized services; and design of complex systems. Only in the third does he add “better design thinking can contribute to achieving an organic flow of experience …” Later, however, he reflects on the list as the “areas of design thinking.” Buchanan appears to use the phrase design thinking as a means to show the expanding influence of design, not as an activity different from design. Design thinking is used as a general term for describing how design is practiced, a way of thinking about what design is, a means to differentiate the way a designer thinks about a problem from the way a scientist thinks about it, the effort of the designer to solve a wicked problem, and to a philosophy of how a product should be designed. He writes that industrial designers stress what is possible, engineers what is necessary, marketing what is contingent on the changing attitudes and preferences of users – each profession uses different arguments in their design thinking. I propose that we abandon “design thinking” as an isolated (and branded) activity distinct from design. Design thinking can refer to thinking generally about design issues or to the way designers think when designing as opposed to other forms of thinking. Design thinking workshops should simply become design workshops or given some other name. The misuse of the phrase may never completely disappear, but I suspect the current backlash may ultimately discourage it. Design thinking should also be distinguished from design method and design process. If design thinking is a unique form of thinking typically used by designers, it must be only one of a few different modes of thought and it must be possible to design without thinking. I will address both these possibilities in the remainder of this article. Design Thinking defined Design thinking as a phrase is useful to describe how designers think and how this type of thinking is different from other forms of thinking. It also distinguishes design as a purposeful activity to find a solution from a design emerging from a purely iterative and evolutionary activity. I suggest that design thinking should describe a unique way of thinking distinct from other forms of thinking. Design thinking relates to the problem-solution interface, the attempt to find a solution to a “wicked” problem, which is a problem not clearly defined. Design thinking is used to discover a finite number of generalized solutions to a problem. Design is an act of creation that asserts a particular embodiment to one conceptual solution. Design thinking is a fundamental and very human way of thinking. It is used by anyone about to make something, plan a party, or organize a trip. However, to do it well requires a great deal of skill and many years of experience. Design thinking typically accompanies design but design is an act of creation that does not necessarily involve any thinking. Symbolic versus analogue thinking The human mind uses two distinct modes of thought, appropriately labelled by psychologist Daniel Kahnman as “fast thinking” and “slow thinking” (Kahneman 2011). Most people tend to use fast thinking to make decisions quickly with very little information or deliberation. Design involves some fast thinking but is mainly slow thinking. The intuitive insight comes quickly but is then verified with a slow deliberate process of modelling and critical evaluation. Fast thinking utilizes simple heuristics. Decisions, made pre-consciously, are often wrong but with a better than chance probability of being right. This ability is critical in a dangerous situation where not acting could be disastrous. Design thinking should involve slow thinking apparatus that serves to critically evaluate proposed solutions, question the problem, and determine the solution space. There is an important distinction between the way designers and the way everyone else, typically engage in slow thinking. I propose that design typically uses a form of slow thinking that utilizes analogy and iconic representations. The other mode of slow thinking I will call symbolic thinking. This is thinking, primarily with language and direct signification, with more symbolic representations. Design thinking workshops typically engage fast thinking modes of participants, and notably, ideas are often presented symbolically as words (on post-it notes) rather than icons. Ironically, this suggests that much of what occurs in design thinking workshops is ordinary (symbolic) thinking, not real design thinking. It is likely that iconic thinking came before symbolic thinking in our evolution and is a natural way to think, the thinking that occurs while dreaming. Communication regarding something new occurs by pointing out an analogy to something already understood. Design exploits this natural iconic thinking in order to discover new concepts that are beyond conventional experience, and conceives or constructs models that are a direct analogy to reality. More specifically, designers will often construct analogues such as sketches, models, and prototypes to describe and solve problems. Symbolic thinking involves a combination of symbols – words or mathematical symbols that have agreed meanings. This form of thinking is fine for the solution of most problems and very efficient for transmitting information from one person to another. However, it is limiting when attempting to solve more complex or “wicked” problems. With symbolic thinking, symbols with previously agreed meanings are combined to consider options and to communicate. Iconic thinking is still required for new concepts or for ideas too subtle for the agreed upon symbology. Metaphoric thinking is found in artistic works including even literary works composed of language symbols. Design uses a form of metaphoric thinking that is more literal and solution focused. It is possible to solve some design challenges with symbolic thinking. A conventional house, for example, can be designed by exclusively referring to plans of existing houses and incorporating the best features of each. Language can be used to approximate a design quickly. “Red, convertible, compact automobile” creates a more specific image in the mind than just “automobile,” but the technique is limiting if trying to design a new automobile.

Design is thus the use of icons including analogy, models, and prototypes. Instead of using reason, consensus, and past experience to solve problems, designers construct an analogous reality that is more subtly expressed, accessible, and modifiable in order to better understand the problem and to experiment with alternative solutions. Symbolic thinking is used to decide between alternative conventional design solutions and to present and prioritize ideas.

Human thought occurs with a string of associations, meaning through convention, metaphor, and analogy. Words appear to have unique meanings but really the meaning of each word changes subtly with context and a string of these meanings create an even more subtle inference that a computer program struggles to interpret. Symbolic thinking, or the use of language for thinking, results in an instant answer to a problem as it is based on an accepted meaning of the symbols. The use of language, which involves not only symbols with precisely denoted meanings, but also multiple connotations, can be used as a metaphorical means to represent reality in a more analogue way. There is thus a spectrum of possible thinking, from a purely symbolic (language without the use of metaphor) representation of reality, to direct analogue representations utilizing models and prototypes. In between is a metaphorical language that seeks a more particular and accurate representation. Design thinking is thinking analogously in order to solve a difficult and contextual problem. In contrast, symbolic thinking attempts to solve particular problems with generalizations and conventional agreements. The thinking tends to involve black and white choices rather than more subtle shades of grey. There are thus three distinct categories of thought, well-articulated by Nigel Cross in “Designerly Ways of Knowing” (Cross 1982): The sciences use symbolic languages, study the natural world, and learn techniques for controlled experiment, classification, and analysis. They value objectivity, rationality, neutrality, and are concerned with the truth. The humanities use metaphorical languages and study human experience. They have values of subjectivity, imagination, commitment, and a concern for justice. Designers use iconic languages, analogous modelling, and literal descriptions. Theirs is the study of the artificial world. They must learn techniques of modelling, pattern-formation, and synthesis. They value practicality, ingenuity, empathy, and have a concern for appropriateness. The language of design is modelling, which is equivalent to literacy in the humanities and numeracy in the sciences. Design by Thinking versus Artificial Intelligence Thinking involves a consciousness. So we can assume that computers, regardless of sophistication of programming, do not really think. Incredible advances have been made in Artificial Intelligence (AI). The defeat of the world champion Go player is a remarkable achievement. In order to accomplish this feat, however, the neural network had to be taught by viewing millions of games and then playing against itself for millions more. It would take a human brain several lifetimes to process this amount of information. So apparently, the brain is able to learn much more efficiently, and make decisions much more accurately, based on far less information available to it. AI systems have a long way to go before achieving human-like intelligence (called Artificial General Intelligence or AGI). This is the ability to perform general intelligent action or the ability to think and experience consciousness. The current AI systems simply iterate endlessly, checking for solutions accurately and flawlessly. The advantage of human intelligence and perhaps the basis of consciousness is the ability to make decisions quickly based on little information.

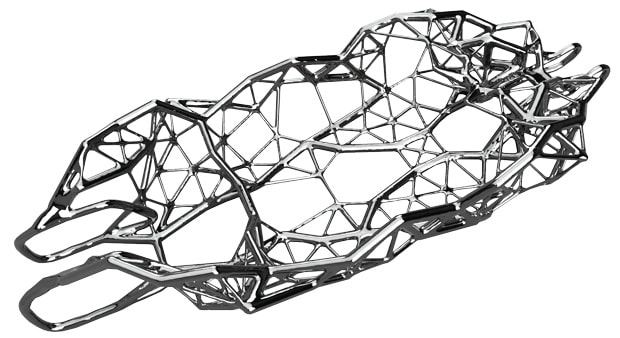

Artificial Intelligence can be creative. Autodesk claims that its software has been used to create the first AI engineered racing car (Autodesk, 2017). Hack Rod and Autodesk took data from sensors attached to a custom car that measured strains and stresses. That data was then fed into Dreamcatcher, which created a new body design, which improved the vehicle’s ability to withstand those stresses. However, it was a partnership of design thinking, artificial intelligence, and virtual reality that created the new design. Creativity is not limited to human intelligence but, so far, thinking is. Humans are required to decide what to make, how something should be made, and what technology should be used to aid in the design process. Computers can design but not think. The distinction between human intelligence and artificial intelligence is clarified by the distinction between design thinking and design.

For designers, I would place less emphasis on the worth of an uncritical iterative design process – “fail fast and iterate quickly.” The craft basis of design, in contrast to AI, suggests that there is a strong desire to succeed. Prototypes do fail and this is not a bad thing. Something is always learned and redesign always results in significant improvements. But multiple failure is not the goal as it is with evolutionary processes. Design thinking is used to narrow down the field and find the direction of success, not to iterate blindly. Artificial intelligence takes a random stab in the dark in a long process of elimination in order to eventually find the right solution. The algorithms of AI achieve success only with an inefficient process of trial and error. The inefficiency is hidden by a limitless capacity for memory and repetition. The difference between thinking design processes and design without thinking Design and making generally involve thinking. However, systems of artificial intelligence can design without thinking by embarking on limitless iterations that gradually converge on an optimum solution. Thinking is the mental process that occurs before doing and before making. The problem-solution interface is the crux of what design is. Idea generation, on the other hand, can be based on a more mindless process like brainstorming, used to discover as many ideas as possible. Brainstorming is summarized as a formal process to generate as many ideas as possible without critical evaluation, in the hope that one of the ideas will be a good one. The premise is that a large quantity of ideas will include some high quality ideas and that many participants will generate more ideas. While, some scientific evidence suggests that individuals working on their own for an equivalent length of time will generate more good ideas (Chamorro-Premuzic 2015), brainstorming, if conducted correctly, with good facilitation, opportunity for individual thinking, as well as group participation, can be an efficient way of finding the good idea missed by other methods (Isaksen, 1998). From a design point of view, idea generation (ideation) is not the most difficult problem. There are a variety of techniques for generating ideas and if sufficient time is allowed for incubation, it can be assumed that all relevant ideas for a given design problem will emerge. The difference between a good design and a bad design is usually determined more by the way the design problem is defined than by the number of ideas. Design utilizes a form of thinking that designers use that is different from ordinary thinking. Design thinking involves the use of iconic representations or direct descriptions to describe and develop a different possible reality. It involves a literal translation of an imaginary reality and typically does not rely on symbols or metaphors. Design thinking is thinking critically and strategically about a problem in an effort to first determine the right problem to solve and second, to discover an exhaustive list of potential solutions. Designing occurs when the concept or solution is known. To design is to decide on a particular embodiment of a conceptual solution out of an infinite number of possibilities. Design is a combination of divergent thinking – determining all the solutions to the design problem in a finite solution space and convergent thinking – determining the particular design of the design solution in an infinite solution space. It is possible, using an AI approach, to design without thinking – design, using a purely iterative approach without much thought. The craftsman iterates; each completed version is an improvement over the last but by engaging intimately with the process in a critical way, the intention is to succeed, not to fail. Design thinking is the attempt to anticipate failure and to make modifications and adjustments before something is made. It ensures that design is a skill based craft rather than an unintelligent process. A good problem is one where there is an obvious choice of solutions. Thinking – using symbols or language – involves political debate and deciding which solution is best. A bad problem is one that cannot be easily solved because of a lack of consensus even though the solution is obvious. A bad problem in the world is that despite many obvious solutions, decisions are still not being made. Symbolic thinking stalls on wicked problems and sometimes turns good problems into bad problems. Opinions swirl on social media but nothing happens. Action is blocked by constant disagreement. Design thinking that uses iconic methods to go beyond the conventional can help to shift debate, to look at the problem from a different angle, and to suggest a new solution.

There is a tendency to present design thinking as a linear process such as Stanford University's empathize, define, ideate, prototype, and test. This deemphasizes the importance of the judgement and skill of the designer and puts too much faith in ideation and testing. The random generation of ideas in an ideation process prevents an informed evolution of understanding. In the following article, I suggest that design thinking is a basic thinking skill—unfortunately ignored in basic education—that everyone already has, and is a circular rather than a linear process.

From 1976 to 1979, I studied industrial design at the Royal College of Art in London, England while Bruce Archer was head of the Design Research Department there. Archer believed that “there exists a designerly way of thinking and communicating that is both different from scientific and scholarly ways of thinking and communicating, and as powerful as scientific and scholarly methods of enquiry when applied to its own kinds of problems.” He was arguably the first author to use the now common phrase “design thinking.” Archer was also concerned with designers’ place in society, especially in education. He noted the three Rs—reading, writing, and ‘rithmetic—with reading and writing both referring to language, betray a prejudice against the doing and making professions. The phrase was apparently derived from a speech given by Sir William Curtis, an English Member of Parliament in about 1825, where he listed:

It seems probable that this was shortened, over the years first to reading, reckoning, and wrighting, and finally, reading, writing, and ‘rithmetic. The ability to make things was still an important aspect of society in the 19th century. But as the industrial revolution gathered steam, manufacturing took over much of this responsibility. Industrial design became a vital but somewhat obscure profession responsible, not for making, but for generating the plans for making. At the time, doing and making were important parts of people’s lives. With the industrial revolution, design replaced making as a formal and professional vocation and basic education concentrated on language and science as the primary means of thought. Archer was convinced that design should stand equal against the sciences and the humanities. He wrote prophetically in 1979, “modern society is faced with problems such as the ecological problem, the environmental problem, the quality-of-urban-life problem … which demand … competence in something else besides literacy and numeracy … a level of awareness of the issues of the material culture.”[1] These problems of the material culture—including economics and the environment—are problems that require a design perspective. Nigel Cross, another British design researcher, in a series of articles about “designerly ways of knowing,” argues that we are all capable of designing; “… design thinking is something inherent within human cognition; it is a key part of what makes us human.”[2] The difference between design thinking and the scientific method is inadvertently described in Robert Persig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. “Actually I’ve never seen a cycle-maintenance problem complex enough really to require full-scale formal scientific method. Repair problems are not that hard.”[3] Doing, making, repairing, and designing all require design thinking. What distinguishes design thinking from the scientific method is not the difficulty of the problem but the degree of definition. In order to apply the scientific method it is necessary to understand exactly what the problem is. The problem is clear, the solution difficult. With repair, it is the problem that is obscure. Once the problem is known, Persig is right; the solution is generally fairly obvious. The process of design thinking is really ordinary thinking that most people use to solve most everyday problems.

With design thinking, understanding evolves as different solutions are tried. With improved understanding, the quality of the solution also improves. In Zen and the Art of Motor Cycle Maintenance, Persig struggles with the definition of quality, at one point saying quality cannot be defined even though everyone knows what it is. I would define quality as a balance of conflicting demands.

A good knife is not so hard that it is brittle or so soft that it bends. Rather it is tempered to the right amount. The right amount is a matter of judgement. This condition is readily apparent when making something. A screw is not tightened so much that the threads strip or left so loose that the parts held together rattle. Robert Persig notes how Jules Henri Poincaré in his landmark book Foundations of Science realized how scientists had to preselect facts from an infinity of possible facts in order to make breakthrough scientific discoveries. This preselection of facts is not arbitrary, but guided by judgements of quality that are, in essence, design thinking. “The difference between a good mechanic and a bad one, like the difference between a good mathematician and a bad one, is precisely this ability to select the good facts from the bad ones on the basis of Quality.”[4] The scientific method cannot help us when no solution is apparent because we do not know precisely what the problem is. Persig refers to this as being “stuck.” “If you want to build a factory, or fix a motorcycle, or set a nation right without getting stuck, then classical, structured dualistic subject-object knowledge, although necessary, isn’t enough. You have to have some feeling for the quality of the work. You have to have a sense of what’s good.”[5] Robert Persig does not mention design thinking or industrial design in Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, but the book did become a sort of manifesto for industrial designers in the ‘70s and ‘80s. We strove for “Good Design,” usually focused on the user experience. Industry was all too happy to comply. By focusing on providing a good user experience, they could sell more products while working behind the scenes to minimize cost by reducing other less apparent qualities. Reducing product quality was not the goal, but it was the result. User centred design has focused too much on the experience of buying the product and less on more important long-term qualities. Superficial aesthetics, appealing point-of-sale displays, and better packaging has encouraged people to buy apparently higher quality, but actually lower quality, products. For this reason, most products are thrown away before they wear out. Quality is more apparent with doing and making. When products are made by hand, determining the quality is easy and there is generally not a problem with user experience. But when a product is made by machine, reproduced precisely, thousands of times, the quality is less obvious. Quality is abstract and wholly dependent on the judgement of the designer. Quality exists only because of design. Quality refers to human decisions, human judgement, and skill. A manufactured product has quality according to the decisions made: quality by design. Without this quality, high volume manufacturing only offers consistency and precision. Industry has focused on reducing production cost, increasing the volume of production, and using the cheapest materials possible. For every high quality expensive product, there are hundreds of lower quality options. Corporations compete to provide the cheapest product, motivating an economy of steadily increasing quantity of production without real increases in prosperity. Other qualities beneath the surface of products must become the focus of design. Instead of just Good Design, we require Lasting Quality with Better Design. Quality decisions are required, not only for the design of products, but also for other areas of the economy. In my book Rationing Earth, I suggest that design thinking could be used to improve the economy. Obvious problems of pollution, growing populations, diminishing resources, and the threat of climate change, point to a need to limit or ration environmental impact. This can be done in such a way that prosperity continues to increase by:

Scientific thinking is applied to well defined problems, but in general can only go so far. An economist can determine how the economy works, but someone still has to decide how the economy should be structured. The combination of a changing environmental context and revolutionary new technologies point to an acute need for new design thinking to solve the problems of the economy. The need for a circular economy suggests the need for a circular design process. Current understanding suggests solutions but those solutions should inform a new understanding and a constant evolution of new ideas.

[1] Bruce Archer, “Whatever Became of Design Methodology and The Three Rs,” Design Studies, Vol. 1, No. 1, July 1979.

[2] Nigel Cross, Design Thinking: Understanding how Designers Think and Work, (Oxford, New York: Berg, 2011), 6. [3] Robert M. Persig, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance: An Inquiry into Values, (New York: Bantam Books, 1974),93 [4] Ibid, 253 [5] Ibid, 255 |

AuthorHerb Bentz is an industrial designer and a founding partner at Form3 Design, a company in Vancouver, Canada that has a strong commitment to the design of ecologically sustainable products. He holds degrees in science, architecture, and industrial design. Archives

January 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed