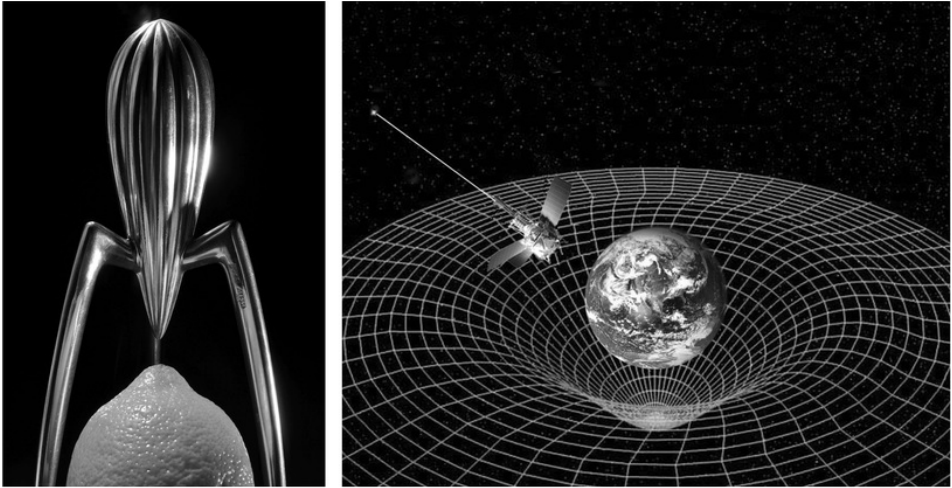

Left: Philippe Starck’s ‘Juicy Salif” lemon squeezer for Alessi; Right: artist’s conception of four dimensional space-time around Earth.[4]

Left: Philippe Starck’s ‘Juicy Salif” lemon squeezer for Alessi; Right: artist’s conception of four dimensional space-time around Earth.[4]

Design Thinking

From 1976 to 1979, I studied industrial design at the Royal College of Art in London, England while Bruce Archer was head of the Design Research Department there. Archer believed that “there exists a designerly way of thinking and communicating that is both different from scientific and scholarly ways of thinking and communicating, and as powerful as scientific and scholarly methods of enquiry when applied to its own kinds of problems.” He was arguably the first author to use the now common phrase “design thinking.”

Archer was also concerned with designers’ place in society, especially in education. He noted the three Rs—reading, writing, and ‘rithmetic—with reading and writing both referring to language, betray a prejudice against the doing and making professions. He claimed a great-aunt always said that the three Rs originally referred to reading and writing (language), reckoning and figuring (numbers), and wroughting and wrighting (the ability to make something)[1]. Archer was convinced that design should stand equal against the sciences and the humanities. He wrote prophetically in 1979, “modern society is faced with problems such as the ecological problem, the environmental problem, the quality-of-urban-life problem … which demand … competence in something else besides literacy and numeracy … a level of awareness of the issues of the material culture.”[2] These problems of the material culture—including economics and the environment—are problems that require a design perspective.

Design thinking, instead of a category of thought, is often presented as a special technique invented by designers that will lead to innovations if used as directed, leading to justified criticisms that design is not the only profession capable of thinking.[3] Critical musings of mathematicians, ruminations of engineers, or the quiet contemplation of anthropologists could be brought to bear on the world’s problems. Design is not an artificial method, but a natural process used routinely by everyone to solve most everyday problems. What designers bring to the table is a specialization in design thinking, honed with years of experience and augmented with an ability to generate models and prototypes to evaluate solutions.

Design is a method of problem solving distinct from the scientific method. Scientific analysis leads logically to a single solution. For the designer, this single solution is just the starting point that must be elaborated on according to detailed requirements of a specific context. Nigel Cross, another British design researcher, in a series of articles about “designerly ways of knowing,” argues that we are all capable of designing; “… design thinking is something inherent within human cognition; it is a key part of what makes us human.”

The difference between scientific analysis and design thinking is not so much a difference in the method used, but in the type of problem solved and in what constitutes a solution. Horst Rittel, a mathematician, design theorist, and university professor at the Ulm School of Design in Germany, suggested that most of the problems addressed by designers are “wicked problems”—those poorly defined and intertwined with solutions. In other words, a wicked problem cannot be understood completely without at the same time considering a possible solution. Solutions cannot be true or false; they can only be good or bad. There is no ultimate solution; every solution suggests a new understanding of the problem and this new understanding leads to a better solution. Another characteristic of wicked problems is that it is not possible to identify a single solution applicable to many similar problems. Instead, an infinity of solutions exists that are each good or bad, but not wrong. This solution focus means that the designer, in addressing a problem, continuously oscillates between trying to understand the problem and suggesting a solution.

What we gain with design thinking are possible concrete solutions before there is full understanding of the problem. We incorporate technology and scientific analysis in design thinking, but usually a leap of faith ignores some information and extrapolates other data—a “short circuit” of analysis that presents a concept for an actual solution that is possibly wrong, but leads more efficiently to one that is right. The premise in design thinking is that any action is sometimes better than no action because, as Thomas Edison believed, there are no failures, just many successes of finding different ways for something not to work. The major difference between scientific analysis and design thinking is that understanding of the problem is never complete with design. Whereas scientific analysis fails when the model fails to represent reality, design uses models and prototypes—representing a future reality—to optimize many variables through successive approximations to solutions.

Philippe Starck, the famous French industrial designer, tells how a “vision of a squid-like lemon squeezer” suddenly came to him while sitting in a restaurant, leading to the iconic product by Alessi.[5] But design thinking—the flash of insight that results from seeing the problem from a different angle—is not restricted to designers. Albert Einstein solved a problem of relativity—how the speed of light can be constant even though different sources of light are moving at different velocities—by realizing that the rate of time passing is what must vary.[6] Instead of the constant speed of light being the problem, it was our perception of time.

Einstein also wryly observed that we can’t solve problems by using the same kind of thinking we used when we created them. Design is a form of thinking and the complement to scientific analysis. The scientist believes that by thoroughly understanding the problem, the solution will be obvious. The designer searches for practical solutions without understanding the problem completely.

The belief that the economy is determined by a scientific theory and therefore does not have to be modified to suit changing contexts—of resource depletion including peak oil, technological change, and new competition from developing countries—not only explains the failure of mainstream economists to predict the 2008 crisis, but likely contributed to its occurrence. Of the failure, Paul Krugman maintained that economists “mistook beauty for truth.”[7] James Galbraith responds in a recent book that such an admission is damaging to the profession and places doubt as to the “place of economics among the sciences.”[8]

What should be designed and what should be allowed to ebb and flow naturally, like water in a stream, is a matter of practicality. The thinking that I would prefer to call design thinking is common to all doing and making professions, and design is simply the act of finding a solution to a poorly defined or “wicked” problem. Design emerges out of necessity. Cities can evolve naturally but at some point the random sprawl becomes unmanageable. The economy has also evolved randomly under the guidance of various scientific theories. Eventually society must decide, specifically, what type of economy it needs or wants. In this book, I argue that point is now.

From 1976 to 1979, I studied industrial design at the Royal College of Art in London, England while Bruce Archer was head of the Design Research Department there. Archer believed that “there exists a designerly way of thinking and communicating that is both different from scientific and scholarly ways of thinking and communicating, and as powerful as scientific and scholarly methods of enquiry when applied to its own kinds of problems.” He was arguably the first author to use the now common phrase “design thinking.”

Archer was also concerned with designers’ place in society, especially in education. He noted the three Rs—reading, writing, and ‘rithmetic—with reading and writing both referring to language, betray a prejudice against the doing and making professions. He claimed a great-aunt always said that the three Rs originally referred to reading and writing (language), reckoning and figuring (numbers), and wroughting and wrighting (the ability to make something)[1]. Archer was convinced that design should stand equal against the sciences and the humanities. He wrote prophetically in 1979, “modern society is faced with problems such as the ecological problem, the environmental problem, the quality-of-urban-life problem … which demand … competence in something else besides literacy and numeracy … a level of awareness of the issues of the material culture.”[2] These problems of the material culture—including economics and the environment—are problems that require a design perspective.

Design thinking, instead of a category of thought, is often presented as a special technique invented by designers that will lead to innovations if used as directed, leading to justified criticisms that design is not the only profession capable of thinking.[3] Critical musings of mathematicians, ruminations of engineers, or the quiet contemplation of anthropologists could be brought to bear on the world’s problems. Design is not an artificial method, but a natural process used routinely by everyone to solve most everyday problems. What designers bring to the table is a specialization in design thinking, honed with years of experience and augmented with an ability to generate models and prototypes to evaluate solutions.

Design is a method of problem solving distinct from the scientific method. Scientific analysis leads logically to a single solution. For the designer, this single solution is just the starting point that must be elaborated on according to detailed requirements of a specific context. Nigel Cross, another British design researcher, in a series of articles about “designerly ways of knowing,” argues that we are all capable of designing; “… design thinking is something inherent within human cognition; it is a key part of what makes us human.”

The difference between scientific analysis and design thinking is not so much a difference in the method used, but in the type of problem solved and in what constitutes a solution. Horst Rittel, a mathematician, design theorist, and university professor at the Ulm School of Design in Germany, suggested that most of the problems addressed by designers are “wicked problems”—those poorly defined and intertwined with solutions. In other words, a wicked problem cannot be understood completely without at the same time considering a possible solution. Solutions cannot be true or false; they can only be good or bad. There is no ultimate solution; every solution suggests a new understanding of the problem and this new understanding leads to a better solution. Another characteristic of wicked problems is that it is not possible to identify a single solution applicable to many similar problems. Instead, an infinity of solutions exists that are each good or bad, but not wrong. This solution focus means that the designer, in addressing a problem, continuously oscillates between trying to understand the problem and suggesting a solution.

What we gain with design thinking are possible concrete solutions before there is full understanding of the problem. We incorporate technology and scientific analysis in design thinking, but usually a leap of faith ignores some information and extrapolates other data—a “short circuit” of analysis that presents a concept for an actual solution that is possibly wrong, but leads more efficiently to one that is right. The premise in design thinking is that any action is sometimes better than no action because, as Thomas Edison believed, there are no failures, just many successes of finding different ways for something not to work. The major difference between scientific analysis and design thinking is that understanding of the problem is never complete with design. Whereas scientific analysis fails when the model fails to represent reality, design uses models and prototypes—representing a future reality—to optimize many variables through successive approximations to solutions.

Philippe Starck, the famous French industrial designer, tells how a “vision of a squid-like lemon squeezer” suddenly came to him while sitting in a restaurant, leading to the iconic product by Alessi.[5] But design thinking—the flash of insight that results from seeing the problem from a different angle—is not restricted to designers. Albert Einstein solved a problem of relativity—how the speed of light can be constant even though different sources of light are moving at different velocities—by realizing that the rate of time passing is what must vary.[6] Instead of the constant speed of light being the problem, it was our perception of time.

Einstein also wryly observed that we can’t solve problems by using the same kind of thinking we used when we created them. Design is a form of thinking and the complement to scientific analysis. The scientist believes that by thoroughly understanding the problem, the solution will be obvious. The designer searches for practical solutions without understanding the problem completely.

The belief that the economy is determined by a scientific theory and therefore does not have to be modified to suit changing contexts—of resource depletion including peak oil, technological change, and new competition from developing countries—not only explains the failure of mainstream economists to predict the 2008 crisis, but likely contributed to its occurrence. Of the failure, Paul Krugman maintained that economists “mistook beauty for truth.”[7] James Galbraith responds in a recent book that such an admission is damaging to the profession and places doubt as to the “place of economics among the sciences.”[8]

What should be designed and what should be allowed to ebb and flow naturally, like water in a stream, is a matter of practicality. The thinking that I would prefer to call design thinking is common to all doing and making professions, and design is simply the act of finding a solution to a poorly defined or “wicked” problem. Design emerges out of necessity. Cities can evolve naturally but at some point the random sprawl becomes unmanageable. The economy has also evolved randomly under the guidance of various scientific theories. Eventually society must decide, specifically, what type of economy it needs or wants. In this book, I argue that point is now.